Understanding how checkpointing works in HDFS can make the difference between a healthy cluster or a failing one.

Checkpointing is an essential part of maintaining and persisting filesystem metadata in HDFS. It’s crucial for efficient NameNode recovery and restart, and is an important indicator of overall cluster health. However, checkpointing can also be a source of confusion for operators of Apache Hadoop clusters.

In this post, I’ll explain the purpose of checkpointing in HDFS, the technical details of how checkpointing works in different cluster configurations, and then finish with a set of operational concerns and important bug fixes concerning this feature.

Filesystem Metadata in HDFS

To start, let’s first cover how the NameNode persists filesystem metadata.

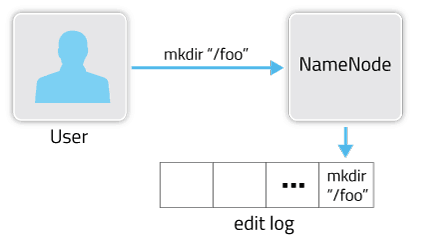

HDFS metadata changes are persisted to the edit log.

At a high level, the NameNode’s primary responsibility is storing the HDFS namespace. This means things like the directory tree, file permissions, and the mapping of files to block IDs. It’s important that this metadata (and all changes to it) are safely persisted to stable storage for fault tolerance.

This filesystem metadata is stored in two different constructs: the fsimage and the edit log. The fsimage is a file that represents a point-in-time snapshot of the filesystem’s metadata. However, while the fsimage file format is very efficient to read, it’s unsuitable for making small incremental updates like renaming a single file. Thus, rather than writing a new fsimage every time the namespace is modified, the NameNode instead records the modifying operation in the edit log for durability. This way, if the NameNode crashes, it can restore its state by first loading the fsimage then replaying all the operations (also called edits or transactions) in the edit log to catch up to the most recent state of the namesystem. The edit log comprises a series of files, called edit log segments, that together represent all the namesystem modifications made since the creation of the fsimage.

As an aside, this pattern of using a log for incremental changes on top of another storage format is quite common for traditional filesystems. Log-structured filesystems take this to an extreme and use just a log for persisting data, but more common journaling filesystems like EXT3, EXT4, and XFS support writing changes to a journal before applying them to their final locations on disk.

Why is Checkpointing Important?

A typical edit ranges from 10s to 100s of bytes, but over time enough edits can accumulate to become unwieldy. A couple of problems can arise from these large edit logs. In extreme cases, it can fill up all the available disk capacity on a node, but more subtly, a large edit log can substantially delay NameNode startup as the NameNode reapplies all the edits. This is where checkpointing comes in.

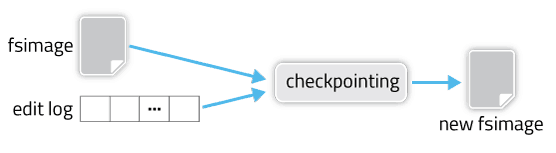

Checkpointing is a process that takes an fsimage and edit log and compacts them into a new fsimage. This way, instead of replaying a potentially unbounded edit log, the NameNode can load the final in-memory state directly from the fsimage. This is a far more efficient operation and reduces NameNode startup time.

Checkpointing creates a new fsimage from an old fsimage and edit log.

However, creating a new fsimage is an I/O- and CPU-intensive operation, sometimes taking minutes to perform. During a checkpoint, the namesystem also needs to restrict concurrent access from other users. So, rather than pausing the active NameNode to perform a checkpoint, HDFS defers it to either the SecondaryNameNode or Standby NameNode, depending on whether NameNode high-availability is configured. The mechanics of checkpointing differs depending on if NameNode high-availability is configured; we’ll cover both.

In either case though, checkpointing is triggered by one of two conditions: if enough time has elapsed since the last checkpoint (dfs.namenode.checkpoint.period), or if enough new edit log transactions have accumulated (dfs.namenode.checkpoint.txns). The checkpointing node periodically checks if either of these conditions are met (dfs.namenode.checkpoint.check.period), and if so, kicks off the checkpointing process.

Checkpointing with a Standby NameNode

Checkpointing is actually much simpler when dealing with an HA setup, so let’s cover that first.

When NameNode high-availability is configured, the active and standby NameNodes have a shared storage where edits are stored. Typically, this shared storage is an ensemble of three or more JournalNodes, but that’s abstracted away from the checkpointing process.

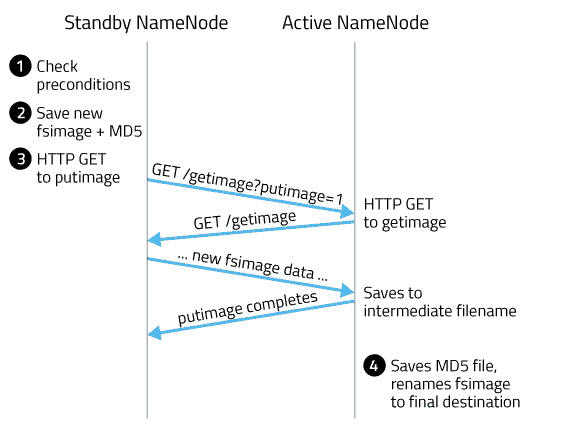

The standby NameNode maintains a relatively up-to-date version of the namespace by periodically replaying the new edits written to the shared edits directory by the active NameNode. As a result, checkpointing is as simple as checking if either of the two preconditions are met, saving the namespace to a new fsimage (roughly equivalent to running `hdfs dfsadmin -saveNamespace` on the command line), then transferring the new fsimage to the active namenode via HTTP.

Checkpointing with NameNode HA configured

Here, Standby NameNode is abbreviated as SbNN and Active NameNode as ANN:

- SbNN checks whether either of the two preconditions are met: elapsed time since the last checkpoint or number of accumulated edits.

- SbNN saves its namespace to an a new fsimage with the intermediate name

fsimage.ckpt_, where txid is the transaction ID of the most recent edit log transaction. Then, the SbNN writes an MD5 file for the fsimage, and renames the fsimage tofsimage_. While this is taking place, most other SbNN operations are blocked. This means administrative operations like NameNode failover or accessing parts of the SbNN’s webui. Routine HDFS client operations (such as listing, reading, and writing files) are unaffected as these operations are serviced by the ANN. - SbNN sends an HTTP

GETto the active NN’sGetImageServletat/getimage?putimage=1. The URL parameters also have the transaction ID of the new fsimage and the SbNN’s hostname and HTTP port. - The active NN’s servlet uses the information in the

GETrequest to in turn do its ownGETback to the SbNN’sGetImageServlet. Similar to the standby, it first saves the new fsimage with the intermediate namefsimage.ckpt_, creates the MD5 file for the fsimage, and then renames the new fsimage tofsimage_.

Checkpointing with a SecondaryNameNode

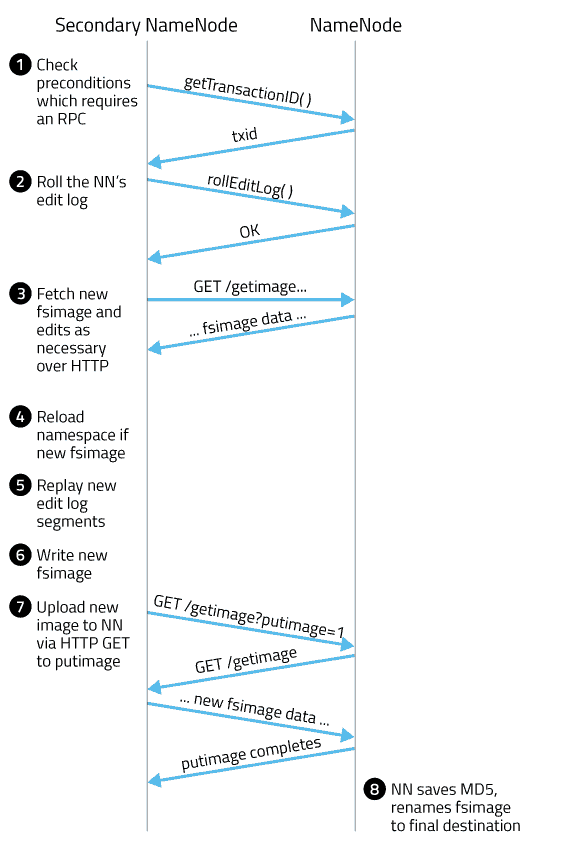

In a non-HA deployment, checkpointing is done on the SecondaryNameNode rather than the standby NameNode. Since there isn’t a shared edits directory or automatic tailing of the edit log, the SecondaryNameNode has to go through a few more steps first to refresh its view of the namespace before continuing down the same basic steps.

Time diagram of 2NN and NN with annotated steps

Here, the NameNode is abbreviated as NN and the SecondaryNameNode as 2NN:

- 2NN checks whether either of the two preconditions are met: elapsed time since the last checkpoint or number of accumulated edits.

- In the absence of a shared edit directory, the most recent edit log transaction ID needs to be queried via an explicit RPC to the NameNode (

NamenodeProtocol#getTransactionId).

- In the absence of a shared edit directory, the most recent edit log transaction ID needs to be queried via an explicit RPC to the NameNode (

- 2NN triggers an edit log roll, which ends the current edit log segment and starts a new one. The NN can keep writing edits to the new segment while the SNN compacts all the previous ones. This also returns the transaction IDs of the current fsimage and the edit log segment that was just rolled. Explicit triggering of an edit log roll is not necessary in an HA configuration, since the standby NameNode periodically rolls the edit log orthogonal to checkpointing.

- Given these two transaction IDs, the 2NN fetches new fsimage and edit files as needed via

GETto the NN’sGetImageServlet. The 2NN might already have some of these files from a previous checkpoint (such as the current fsimage). - If necessary, the 2NN reloads its namespace from a newly downloaded fsimage.

- The 2NN replays the new edit log segments to catch up to the current transaction ID.From here, the rest is the same as in the HA case with a StandbyNameNode.

- 2NN writes out its namespace to a new fsimage.

- The 2NN contacts the NN via HTTP GET at

/getimage?putimage=1, causing the NN’s servlet to do its ownGETto the 2NN to download the new fsimage.

Operational Implications

The biggest operational concern related to checkpointing is when it fails to happen. We’ve seen scenarios where NameNodes accumulated hundreds of GBs of edit logs, and no one noticed until the disks filled completely and crashed the NN. When this happens, there’s not much to do besides restart the NN and wait for it to replay all the edits. Because of the potential severity of this issue, Cloudera Manager will warn if the current fsimage is out of date, if the checkpointing 2NN or SbNN is down, as well as if NN disks are close to capacity.

Checkpointing is a very I/O and network intensive operation and can affect client performance. This is especially true on a large cluster with millions of files and a multi-GB fsimage, since copying a new fsimage to the NameNode can eat up all available bandwidth. In this case, the transfer speed can be throttled with dfs.image.transfer.bandwidthPerSec. If you do adjust this parameter, you might also need to adjust dfs.image.transfer.timeout based on your expected transfer time.

If you’re on an older version of CDH, there are also a number of issues related to checkpointing that might make upgrading worthwhile.

- HDFS-4304 (fixed in CDH 4.1.4, 4.2.1, and 4.3.0). Previously, it was possible to write an edit log operation so big that it couldn’t be read when replaying the edit log. This would cause checkpointing and NameNode startup to fail. This was a problem for files with lots of blocks, since closing a file involved writing all the block IDs to the edit log. The fix was to simply increase the size of the maximum allowable edit log operation.

- HDFS-4305 (fixed in CDH 4.3.0). Related to HDFS-4304 above, files with a large number of blocks are typically due to misconfiguration. For example, a user might accidentally set a block size of 128KB rather than 128MB, or might only use a single reducer for a large MapReduce job. This issue was fixed by having the NameNode enforce a minimum block size as well as a maximum number of blocks per file.

- HDFS-4816 (fixed in CDH 4.5.0). Previously, image transfer from the standby NN to the active NN held the standby NN’s write lock. Thus if the active NN failed during image transfer, the standby NN would not be able to failover until the transfer completed. Since transferring the fsimage doesn’t actually modify any namespace data, the transfer was simply moved outside the critical section.

- HDFS-4128 (fixed in CDH 4.3.0). If the 2NN hit an out-of-memory (OOM) exception during edit log replay, it could get stuck in an inconsistent state where it would try replaying the edit log from the incorrect offset during future checkpointing attempts. Since it’s likely that this OOM would keep happening even if we fixed log replay, the 2NN now simply aborts if it fails to replay logs a few times. The underlying fix though is to configure your 2NN with the same heap size as your NameNode.

- HDFS-4300 (fixed in CDH 4.3.0). If the 2NN or SbNN experienced an error while transferring an edits file, it would not retry downloading the complete file later. This process would stall checkpointing, since it’d be impossible to replay the partial edits file. This issue was fixed by first transferring the edits file to a temporary location and then renaming it to its final destination after transfer completes.

- HDFS-4569 (fixed in CDH4.2.1 and CDH4.3.0). Bumped the image transfer timeout from 1 minute to 10 minutes. The default timeout was causing issues for checkpointing with multi-GB fsimages, especially with throttling turned on.

Conclusion

Checkpointing is a vital part of healthy HDFS operation. In this post, you learned how filesystem metadata is persisted in HDFS, the importance of checkpointing to this role, how checkpointing works in both HA and non-HA setups, and finally covered a selection of important fixes and improvements related to checkpointing.

By understanding the purpose of checkpointing and how it works, you are now equipped with the knowledge to debug these kinds of issues in your production clusters.

Andrew Wang is a Software Engineer at Cloudera and a Hadoop committer.